ʌndəˈstandɪŋ/

1) the ability to understand something; comprehension.

2) sympathetic awareness or tolerance.

Do you know what cancer is? I mean really is. Not just ‘that awful fucking disease that hurts people you love’. But what it actually does to the human body at a cellular level? What it is that makes cells suddenly start doing something they aren’t supposed to do? No? Well, you’re not alone. Yes? Then I’m guessing you’ve either been through the cancer mill yourself or been beside someone you care about as they have, and for both of which I’m truly sorry. You may, if you wish, be excused from class.

One of the most difficult things about a cancer diagnosis is understanding what that really means. Most of us don’t have medical degrees or extensive scientific knowledge of the biology and chemistry that drives cancer so it’s hard to grasp what’s happening inside your body that suddenly means you’re facing a life-threatening illness. It’s especially hard to comprehend that there are cellular changes taking place inside you that need rapid and drastic treatment when you’ve had zero symptoms prior to the diagnosis and, apart from the occasional middle-aged ache and pain, you feel fit and well. I mean you’re not Usain Bolt, but you’re still able to get up a few flights of stairs without your chest exploding.

Some people when they’re told they have cancer want to know everything. Read every book they can, Google every word on their doctor’s letters, research the hell out of it because, for them, it’s the better the devil you know. For some there’s comfort to be found in knowing the mechanics of how their cells are mutating and changing, in knowing the latest thinking on cutting edge treatments and interventions. Some want to be entirely on-the-ball so they can actively participate in the decision-making process on how their cancer is tackled by their medical team.

But not everyone wants to know the ins and outs of their diagnosis. Too much research, too much time diving into the Google blackhole can be terrifying so some people prefer to rely on the expertise of the medical staff looking after them. To be guided by the professionals as to what needs to happen, and to let those pros doll out as little or as much information as they think the patient needs to deal with their situation or make a decision about their treatment.

As ever, and much like my taste in music and pop culture, I’m standing squarely in the middle of the road. I’ve, for the most part, resisted the lure of Google, knowing that it can steer you down dark and depressing paths, and have tried to understand my disease based on the information that the doctors and nurses have so far given me. This has mostly been in the form of booklets and pamphlets from a charity called Breast Cancer Care (see my note at the bottom of this page). These leaflets, while overwhelming in number, have proved a lifeline – a source of clear, concise information and explanation. Not too detailed, graphic or complex but enough for me to grasp the basics of what is happening and understand some of the terminology that gets thrown around in the cancer world.

And so as we head into October and Breast Cancer Awareness Month, I thought you might not mind a quick lesson in what sort of breast cancer I have so you can more easily follow the journey that this crappy disease is going to take me on. Because maybe by understanding what cancer is, you’ll understand what cancer does, to the people dealing with it. So get comfortable, I’ll try not to get too sciencey but there might be a quiz at the end (there’s not a quiz at the end):

What is Cancer?

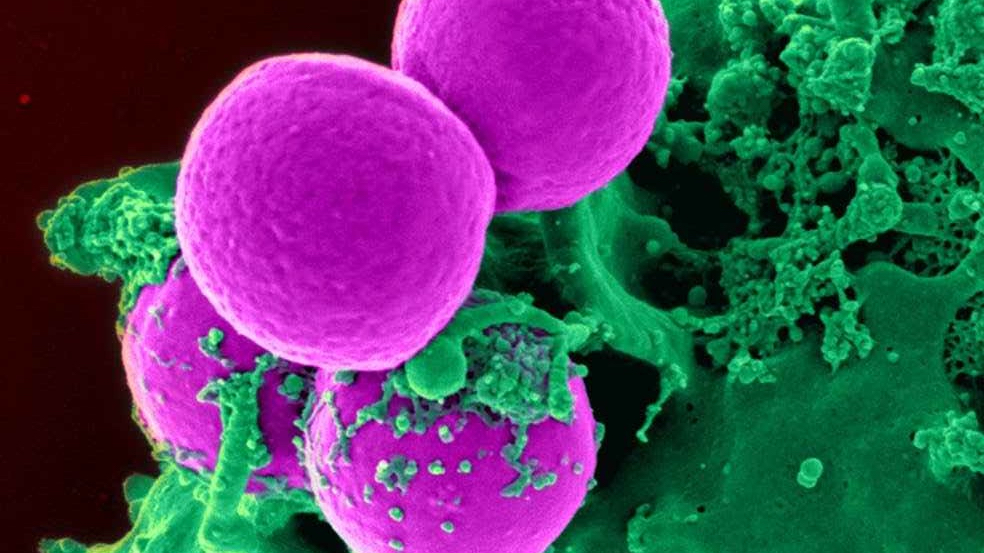

Cancer starts in cells. Not rooms to restrain prisoners but biological cells – think of them as the little Lego brick building blocks that make up our tissue and organs. These cells normally divide to make new cells in a nice, controlled, orderly fashion (now if only Lego bricks did that!) and this is how our bodies heal themselves and grown. But sometimes this orderly cell division goes haywire and the cell becomes weird, abnormal but keeps dividing and makes even more abnormal cells (Daily Mail headline – Lego bricks gone bad!). Eventually these cells form lumps or tumours. Not something you want to step on with bare feet.

A more detailed, professional and less Lego-y explanation of what cancer is can be found here: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/what-is-cancer

Cancer can occur almost anywhere in the body (there are 200 types apparently. Eeek, that’s scary). But mine is boob cancer.

Primary Breast Cancer

I have primary breast cancer. This means this is a breast cancer that has not spread outside the breast or the glands, known as lymph nodes, which are under the arm. Breast cancer can be both invasive and non-invasive. I, lucky son of a gun that I am, have both.

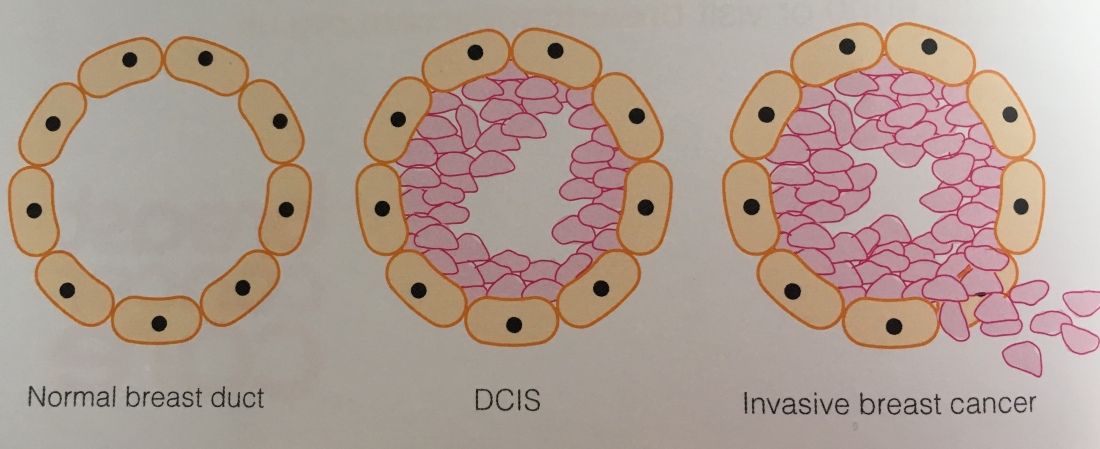

Non-invasive Breast Cancer – Ductal Carcinoma in Situ (DCIS)

If there’s ever a ‘good’ type of breast cancer to have (which there really, really isn’t, so please don’t EVER tell anyone they are ‘lucky’ to have it, and actually let’s just call this the ‘slightly less evil’ type of breast cancer) it’s this one.

Non-invasive simply means it hasn’t yet developed the ability to spread (either inside the boob, or elsewhere in the body) and DCIS is recognised as an early form of breast cancer, which accounts for about 12% of all breast cancers. My original, now ex-surgeon (more later on why he’s now my ex-surgeon) liked to call DCIS ‘pre-cancer’. My Breast Care Nurse dismissed that label as rubbish (she’s pretty kick-ass, we like her).

But DCIS is sometimes known as ‘pre-invasive cancer’. This is simply because the cancer cells are changing and growing within the milk ducts (ie, in situ) and haven’t yet changed to cancer cells which can spread. But that doesn’t mean they can’t or won’t and if DCIS isn’t treated, it may well develop into invasive cancer. Like I said, there’s no ‘good’ cancer and a diagnosis of DCIS can mean just as heavyweight treatment as invasive cancer, including a mastectomy. On the plus side, DCIS, because it is confined to the ducts, has a very good prognosis.

DCIS is graded as low, medium and high. Low means the cancer cells are slow growing, high means fast-growing. Hitting the cancer jackpot again, my DCIS was graded as high. Now is not the time to start excelling in tests Karen.

Invasive Ductal Breast Cancer (of no special type)

Alongside the DCIS, I also have invasive ductal cancer, which simply means the cancer cells started in the milk ducts but made a break for it (the only bit of me that has ever wanted to rebel. Shit choice of subversion Karen) and have now spread to the surrounding breast tissue. IDBC gets the rather derogatory ‘of no special type’ label simply because the cancer cells have no distinctive features that class them as a particular type. It’s almost enough to make you feel sorry for them. Almost. Well, maybe not. F**k those feature-less cancer cells.

There are lots of other types of invasive breast cancer (lobular, inflammatory, Paget’s disease and the rarer tubular, cribriform, medullary, papillary etc, which start to sound like spells from Harry Potter or, put together, a song from Mary Poppins).

Invasive breast cancer also comes in grades (1 to 3) and, luckily for me, I flunked a bit this time and got a 2.

Hormone Receptors and Protein

Breast cells normally and naturally contain proteins known as hormone receptors which receive messages from hormones in the body and react by telling the breast cells what to do. Think of them like Dads when they’re in charge of the kids. They get phonecalls from mums reminding them that the kids have got piano lessons, then the Dads tell the kids to go to piano class. (Apologies to all efficient and organised dads everywhere, sometimes a lazy stereotype is the only way to go).

Sometimes the abnormal breast cancer cells contain receptors that respond to the hormones oestrogen and progesterone and can stimulate the breast cancer to grow. This is definitely not a good thing. All women with invasive breast cancer will be tested for these hormone receptors. If the results are positive it is known as oestrogen receptor positive breast cancer, normally appearing as ER+ (or ER+/PR+ or ER+/PR-), and the likelihood is that once active treatment of the cancer (in the form of surgery/chemo/radiotherapy) has finished then a long course of hormone therapy will also be recommended. Deciding what HT will be used is incredibly complex and depends on a wide range of factors but for me, the most likely outcome will be 5 years taking Tamoxifen. There will undoubtedly more on that to follow.

Some breast cancer cells also have a higher than normal level of a protein called HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 – which sounds like something Charlie Brooker made up on ‘Black Mirror’) on their surface and which stimulates those bastard cells to grow. Again, all invasive breast cancers are tested for this protein when a biopsy is done and if the result is positive chemotherapy is normally recommended.

Luckily, this is another test that I flunked as my cancer was HER2 negative. Phew.

Treatment

So after all that sciencey shit, what’s next? As you can see, breast cancer can vary in so many different factors, it’s not surprising that how it is treated can also vary in a myriad of different ways.

For me, the treatment path was laid out as:

- Surgery – a lumpectomy (or wide local excision) to remove the IDBC tumour and the ducts where DCIS was present;

- Radiotherapy – targeted high energy x-rays which aim to destroy any cancer cells that might remain in the breast are after surgery.

- Hormone therapy – Tamoxifen for 5 years

But nothing in the magical world of cancer is fixed and the sands shift under your feet all the time as tests, scans and biopsies reveal more and more detail about your own personal tumour and rebellious, mutating cells.

So treating my cancer might not be as easy as 1 – 2 – 3.

Next up – S is for Surgery. Roll up, roll up for the delights of wire insertion, nipple injections and vomity lemon squash.

This blog is brilliant! Have been following since the start, the title appealed to me as I love samplers…the embroidered type, ABC and all that.

I’m just out of the surgery/chemotherapy/radiotherapy time, soon to enter the annual checkup time and the fear of reoccurrence time. With the same diagnosis as yourself. I got through using many tools, one being to find something to make me smile each day. (Another being 3l of water each day!).

Your blog is continuing to make me smile….I’m sure it’s being a big help to many others. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the comment Kerry. So pleased to hear it means something to someone who’s had to travel the same path. Here’s wishing all your check ups are clear xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Like!! I blog quite often and I genuinely thank you for your information. The article has truly peaked my interest.

LikeLike